THE WAY I HEAR, Fuchu 2012-2013 / Fuchu Art Museum Open Studio Program 57

OPEN STUDIO@@@@@Listening@@@@@Research@@@@@Performance@@@@@Leaflet

"For just how long can a sound be heard, and how far can it travel?"

text by Ryoko Kamiyama (Curator, Fuchu Art Museum)

Since the 2000s, mamoru has been analyzing various aural experiences hidden within the routines of everyday life in the context of a homogenized living environment that has been largely standardized on a global scale. He draws out the essence of these experiences, reconfigures them in the form of artworks, and presents them at venues around the world. The materials he works with include the sounds emitted by crumpled pieces of plastic wrap, and the sound of water droplets falling from a block of ice as it melts. These sounds, which everyone hears but typically pays little attention to, reaches our ears in a fresh, distinct, and vivid form, thanks to the modest mechanisms that mamoru devises.

In November 2012, mamoru, who lives and works in Fuchu city, finished installing this work for the gOver the Rainbowh exhibition that was being held at the time, and moved into a studio space that was open to the public at the same time that the exhibiton opened. There, he reworked his getude for everyday lifeh, a series that he has been developing for close to ten years, embarking on a new artwork that represents an extension of these previous forays by starting almost from a blank slate, the process of which was open to public view.

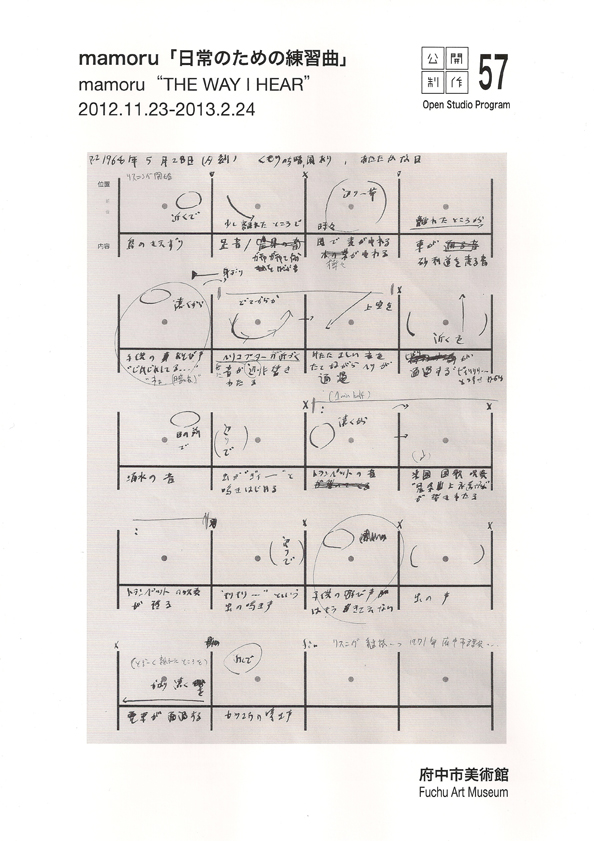

mamoru began by collecting fragments of Fuchufs urban soundscape. Setting out either alone or in a group of several people, he spent ten minutes in each chosen location recording all the sounds that he heard right there on the spot, without verifying their existence through visual means. After returning to the museum, he analyzed the notes and sounds that he had collected, and discussed various ways in which they could be described or recreated.

Photos of all the locations that mamoru had glistenedh to were pasted all over the walls of his open studio, one by one, while other photos that he had obtained from the internet \ in other words, images of places that mamoru had not actually visited himself \ as well as imaginary descriptions of various sounds, were added to the mix.

Parallel to this project, mamoru also conducted wide-ranging oral and documentary research on the history, geography, and ecology of Fuchu, investigating the train routes that were used to transport fuel to military bases in the area, the many underground veins of spring water, the American national anthem that used to play on the US bases, the war era and the postwar period that followed, and Mount Asama. In this way, mamoru imagined the various relationships linking the records and memories pertaining to all the sounds that had emerged around the museum, which was built on the site of a former military base,

In early December, mamoru found himself increasingly fascinated by the life of Tsuneichi Miyamoto (1907\81), a folklore scholar who had lived in Fuchu for a long time (from 1961\81), and who had apparently taken photos of many of the same places that mamoru had visited. In Miyamotofs books, mamoru discovered the cries of the skylarks that used to fly over Fuchu, making up part of the everyday soundscape of Miyamotofs era. These birdcalls are sounds that were heard not far from the museum in Fuchu where we stand now, just over half a century ago \ sounds that we in the present can now hear thanks to Miyamotofs text, or just the intervention of our imagination. This act is what mamoru refers to as gsounds that we can hear even nowh. Sounds are created through the actions and agency of a particular subject. Here, we find the essential beginnings of an artwork that will later be realized as a performance, connected to an act of listening that imagines the sounds that were audible at the places that mamoru photographed.

In late January 2013, mamoru began planning his performance in earnest, diligently rehearsing with a group of other performers throughout the month of February.

Finally, the day of the actual performance arrived. During the first half, all the participants practiced honing gearsh capable of imagining specific sounds through verbal descriptions. In the second half, mamoru orchestrated a truly bizarre experience of space and time that resembled nothing so much as a recitation play by two performers, so strange that it escaped all categorization. Drawing on quotes by Tsuneichi Miyamoto and Doppo Kunikida, and reading aloud from notes detailing his listening experiences and records of city council proceedings, mamoru attempted to express imaginary sounds using verbal descriptions. The recordings were played over speakers installed inside the venue, moving between 1898, 1941, 1968, 2012, and 2013, and the voices and narrators shifted between mamoru, Miyamoto, and members of the city council. Unable to distinguish one time period or speaker from another, the audience was forced to sift through these sounds in a state of confusion. This confusion was definitely not an unpleasant one, however \ there was also something intoxicating about this space-time of multiple, overlapping voices. mamorufs performance, which went on for almost an hour, left behind a quiet reverberation in the ears of the audience before coming to a close.

mamorufs work seeks to transform the way in which we assess the value of sounds. His getude for everyday lifeh takes its cue from sounds that operate in the present tense, so to speak, staging a recreation of actual sounds from reality and destabilizing the space of the here and now that the audience occupies. During the experimental performance that he conceived for this exhibition, verbal descriptions by the various participants served to transport the audiencefs consciousness back to the past, towards a store of memories \ almost as if sounds that previously unfolded in the past had appended themselves to the present. Perhaps it doesn't really matter whether these sounds, contained inside memories, resonated in the same way within the ears of the audience. Our consciousness has already found its way towards these sounds. For just how long can a sound be heard, and how far can it travel? Thanks to mamorufs contrivances, the range of sounds audible to us seems to have widened even more.

(translation: Darryl Wee)